As I’ve continued to explore the question of why some records sound better than others, it’s drawn me to learn more about how records are made. With no first hand knowledge of my own about this process, I thought it best to seek input from professionals who know it intimately.

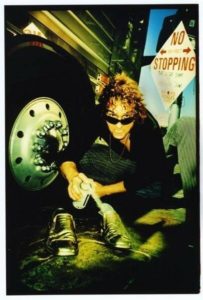

Bobby Macintyre has been in the music business for as long as I’ve known him, so when I heard he had set up his own recording studio in Miami, Florida I knew I had to reach out.

TBR: I know you’ve been a musician since at least high school, perhaps even longer. When you did you get into recording and producing and why did you decide to do it?

BM: I found the drums at an early age and was fortunate to be surrounded by other musical kids. I felt very comfortable playing drums from the beginning and loved practicing and playing along to records. As much as I would be listening to the drums, I was always interested in what everyone else was playing as well. I started playing in bands when I was 12.

Pretty soon the form and the way songs were arranged intrigued me, and I started to understand that the mood of a song and the taking of a listener on a journey was the magic. I studied music theory, ear training and I was involved in all styles of music throughout my early teens. Playing with a symphony, jazz bands, rock bands and all styles helped open up my musical taste, and I think this really comes out in many of my productions.

Since I was exposed to so many styles at a young age, I was able to understand how instruments were traditionally used in a musical context. I think all of this early musical experience inspired me to be more than a drummer. When I attended the University of Miami as a Studio Music and Jazz Major, I was playing in original bands around Miami. I also tried to surround myself with poets and writers with real depth. That approach stayed with me throughout my career and has shaped me and the type of artists I work with.

The actual recording process and engineering side of making proper records is something that came natural. Understanding different types of microphones, placement techniques and how each microphone can color a sound is exciting to me and a huge part of what I do.

TBR: How DO you decide which musicians to produce and record? I would think that your approach is not necessarily a fit with every artist.

BM: Producing, recording and developing artists has many layers. I’m interested in working with the ones that live their truth and are honest and unique, artists with their own sense of melody and style, whether they are instrumental or vocal. My goal is to capture the true sounds of instruments and arrange the music, building with ideas that help bring a song together and take the listener on a sonic adventure.

TBR: You mentioned to me before that you produce / engineer artists in an all analog studio. When we spoke the other day you told me that you converted to analog after buying Johnny Cash’s tape console. Do I have that right?

BM: I bought an MCI 416 recording console from Jack Grochmal who worked with Johnny Cash in Tennessee. He aquired the console in the 1970’s and when he was ready to sell, wanted it to go to a good studio with someone who had a similar passion for recording. I utilize the MCI with an Otari MTR 90 2″ tape machine that was in Criteria Recording Studios, now the Hit Factory in North Miami Florida. The recordings I’ve heard when Johnny Cash was utilizing my MCI are some of my favorites!

There were hit records literally recorded on my console! One of which was a song by the artists/songwriters England Dan and John Ford titled “I’d Really Love To See You Tonight.” I loved the idea that a hit song was made on my console, especially a song I knew and remembered being played constantly on the radio as a child.

TBR: That’s very cool! Although there might be some folks who won’t thank you for reminding them about that song. It seems you bought more than just a recording console. You now own a piece of music history! Why did you decide to buy the MCI and convert from recording digitally to recording in an analog format?

BM: I always invested in great microphones and microphone preamps, but I felt that the digital recordings I was making, as good as they sounded, were lacking some depth. I feel that the digital world hits your nervous system different than in the analog realm. Maybe it’s the circuitry, the op amps in the recording console or the tape. When I started recording on the MCI, everything just sounded like a proper record from the beginning of the process. I felt I didn’t need to work as hard to find the sounds and tones I was capturing.

TBR: I know what you mean about recordings that lack depth. And when you say “the digital world hits your NS different than in the analog realm, I relate strongly to that as well. There’s just something that a good analog recording has that’s hard to put your finger on. It’s so great you were able to find that quality with the MCI.

Speaking of the digital world, you spoke the other day about formats designed for modern consumption, such as the MP3, and how they fail so badly to convey the work you do for the listener. You described entire parts of the mix disappearing. It must be very frustrating as an artist to have your work compromised that way.

BM: The experiences I have had with MP3s and compressing tracks to a digital format so they are easily consumed by the listener has never been a favorite. The listener doesn’t get the full sonic spectrum of the recordings. I want the listener to hear what I’m hearing in the studio, whether they’re listening on earbuds or speakers. Quality of sound has always been more important to me than convenience.

TBR: I imagine this is the reason you have the music you produce cut to vinyl instead of just releasing it digitally. As an audiophile and music fan who mostly listens to vinyl, I’ve become very interested in what choices in the process of performing, recording / engineering, mastering and pressing will best convey the artists work to the listener. As a recording artist, have you made certain choices in your work that you’ve made specifically to better engage the listener? If so, can you give and example?

BM: I use real instruments when recording so musicians can breathe dynamically with each other. This really gives the song life. Using real drums and amplifiers for guitars means actual air being pushed. I also never use any sort of auto tuning on a vocal. I really take my time with singers recording vocals, having conversations with the artist whether it’s about pitch, phrasing, attitude or groove. Every idea that is recorded needs to compliment every other.

The musical choices happen from idea one and I tend to mix as I go, making sure there is no “I’ll fix it in the mix” mistake. Panning (left and right automation), volume moves and so many ideas that happen in the mix stage can happen from the beginning of a recording process these days when utilizing protools or other workstations. Utilizing the analog and digital world is not only helpful in the mixing process but editing as well. I feel it’s a big part of making modern records without sucking the soul out of the music.

TBR: I know that the drums have been your main instrument over your career as a performer. As a listener who’s not a musician, I struggle to articulate what a great drummer does for a great recording beyond just recognizing how impactful the drummer’s role is. As my skills as a critical listener have honed, I find that I pay way more attention to what the drummer is doing on a recording and have come to appreciate his or her role so much more in the process. Mick Fleetwood is an example of a drummer I’ve come to appreciate an awful lot. Are there any particular drummers whose work you especially admire?

BM: I’ve always been attracted to drummers that play for the song, whether it’s with simplicity that lets the melody come out without interrupting the flow, the feel and groove, or musical choices they make. Steve Gadd has probably been the biggest influence on me. Steve has been a recording session drummer since the 70’s and is still making records today. I’ve always been interested in creative drummers but more importantly a drummer that has respect for the song.

TBR: Speaking of having a feel and respect for the song, I was so excited when you mentioned that you’d met Bob Ludwig. I’m personally a huge fan of his work, as many are. It’s amazing to me how big an impact a mastering engineer has on the sound of piece of music. It wasn’t that long ago that I’d never even have thought about being a fan of a mastering engineer, but here we are. Are there any mastering engineers whose work you admire?

BM: Yes I had an amazing dinner with the legendary Bob Ludwig a few years ago on my birthday after a Recording Academy event here in Miami Florida. The incredible catalog of music “The Bob” has contributed to to is astounding. Mastering records is such an art and can make or break a mix.

As for other mastering engineers I admire, I’d have to say Robert Vosgien at Capitol Mastering/Capitol Records in Los Angeles. He’s been the mastering engineer for all of my recordings for the past twenty years and is a big part of what I do. I feel lucky to have him on my team.

TBR: I know you’ve been working with Jeff Powell at Sun Studios in Memphis to cut masters for the music you produce and engineer to press to vinyl. What about Jeff’s work do you particularly appreciate?

BM: Jeff Powell is so passionate about cutting masters. Not only is he an exceptional engineer who worked as an assistant to legendary producer/inventor Tom Dowd for many years, but he’s also an accomplished producer himself who has worked on countless recordings.

Jeff was cutting on the original lathe from Stax Records and is now working out of Sun Studios in Memphis, cutting on his own lathe. His communication and attention to detail in that process is priceless. Again, like Bob Vosgien at Capitol, Jeff Powell is part of a team I’ve been fortunate to work with over so many years. The level of trust I have for him, and his mastery and passion for cutting is unmatched.

TBR: Getting back to Bob Ludwig. As you mentioned, he has mastered the work of a staggering array of artists. I’ve personally heard just a small sample of his work, but I’ve particularly enjoyed some of the live albums he’s done. Bowie’s David Live comes to mind. Bob is just so skilled at conveying the scale of instruments relative to each other that is, in my mind, the key to the sound of a live recording. His studio recordings also tend to have a “live in the studio” feel that I find really exciting to listen to. His famous cut of Led Zeppelin’s sophomore album immediately comes to mind. John Bonhams’ drums sound so HUGE on that record!

When you’re recording music, are there particular qualities in the music that you try to bring out in a way that will make listening to the final product, the record, exciting and engaging for the listener? If so, what is an example and how do you go about it?

BM: The environment or rooms are a big part of the end result in a recording. At my recording studio in Miami I have rooms with hardwood floors that are raised and are very live. I also have rooms that are very dry and dead. At the end of the day, if you’re recording in different rooms but using the same microphones and console, there is cohesion with the tape being the glue to pull it all together.

TBR: One quality that myself and other audiophiles’ prize highly in recorded music on vinyl is a sense of studio space around the instruments. It’s this quality that makes the instruments sound real, giving the music that “live in the studio” feel I mentioned. Is this a quality that interests you and, if so, is it one you aspire to convey in your work?

BM: Absolutely. The air around the amps or instruments is just as important as the instrument itself. Vocals as well. You can have the vocalist close to the microphone and get that in your face sound, or have them step away a little bit to capture more of the room. I have a reverb plate that is a big part of the sound of my studio. It is an EMT reverb plate that I have upstairs in a separate room with the remote on my recording console to open it up or close it up making the reverb bigger or smaller depending on my intention. The microphones, the mic preamps on the MCI console, the studio air and rooms as well as the reverb plate are all part of my sound these days.

TBR: You mentioned to me earlier that you will sometimes record certain parts of the music in analog, but continue to record other parts digitally. How do you choose which parts to keep analog and which to record digitally?

BM: I use the analog recording console for recording everything but don’t feel that everything needs to hit actual tape. I make those choices in the process depending on the mood I’m going for as a producer. Sometimes I won’t record the piano to tape because I feel it loses some brightness that I want to hang onto. I rarely record percussion (tambourines, shakers etc..) to tape. It really is dependent on the needs of the song.

TBR: Have you ever had the experience of listening to a vinyl copy of an album you’ve done and, upon hearing it, wish you’d done something different before shipping the master tape? If so, can you give an example?

BM: No. I generally spend about two days on a mix and when it’s ready it’s ready. I don’t second guess myself or go back and re-mix things. I spent enough time on them and have never regretted my decisions. I’m always proud of the records I’ve made and don’t look back. There have been occasions where I’ve had to master a song more than once because I wasn’t happy with the results for one reason or another, but that’s an easy conversation and usually it’s because I lose dynamics when a song is mastered too hot. I really like my records to breathe and I prefer to listen to and hear the intention of the musician. I like soft, loud and everything in between.

Artists often want their songs to jump out of the speakers, and a lot of mastering engineers will just make the track louder by utilizing heavier compression to achieve this. I say if you want to hear the song louder, turn the volume up! I’m a huge fan of dynamics and it’s probably the biggest conversation I have with musicians and artists in general. Again, it saves a lot of frustration in the mixing process if ideas are played and recorded correctly from the beginning.

TBR: It’s interesting to hear what you’re saying about dynamics and compression. The records I find myself playing the most these days are the ones with the most dynamics, but these also the records that require the most volume to fully appreciate.

You’ve offered to send me a vinyl sample of your recent work. I’m really excited to give one of your records a listen!

Thank you Bobby! It’s been great talking with you.

For more information on Bobby and Studio 71, or to contact him, click here.