A dear friend of mine recently sent me a couple of new records as a gift. I sent him an email thanking him for making a generous contribution to what is a GROSSLY under represented segment of my collection – music from the current millennium.

I must admit it makes me feel like I’ve “become my parents” when I realize that I rarely listen to music recorded after 1989. And at the rare times I do listen to current music I generally struggle to comprehend its virtues.

One of the people I follow on Instagram posted a Clash album a while back, describing the seminal band as having “ripped Rock & Roll and new one.” I loved that phrase and commented, leading to a brief exchange that had us exploring the topic of whether any contemporary artists were speaking to the current generation the way The Clash were in their day. He suggested Grimes was such an artist.

So being a huge fan of The Clash, I cued up some Grimes on Spotify, excited to hear a current artist who’s sensibilities I might find similarly satisfying. I think the first track lasted all of 10 seconds before I was scrambling for the stop button. It would seem I am doomed to remain baffled by current popular music for the foreseeable future.

Of course, part of the issue is being an audiophile and the ridiculous standard that sets for any artist who’s work lands on my turntable. And even with “audiophile quality” recordings I am still struggling to put my finger on what it is about modern records, leaving aside what may be insurmountable problems I have with modern music, that always seems to leave me cold.

With the multitude of advantages that contemporary recording engineers would seem to have with access to equipment and many many decades of historical knowledge and experience in recording music, one would expect modern records to easily surpass their vintage relations. Yet they rarely do. Modern records, even those made from very high quality recordings, have IMHO a dry, lifeless quality that manages to sound very real and very dull at the same time.

Last year I posted a conversation with TBR reader and contributor Alex Bunardzic where we hashed out some questions about why modern records are so often disappointing. Alex wondered if it wasn’t a bias created by the sound of CD’s. At the time I wasn’t sure I totally bought into that, but I have noticed since how many “audiophile” records and some well recorded current releases often share a sonic profile with compact discs. In particular, modern records often emphasize a “black background” with instruments and vocals presented in stark contrast to that background, giving the performance an attention grabbing hyper-realism.

Clearly these recordings are done in a studio, but there seems to be a deliberate attempt to remove the sound of the studio space from the recording. The result is striking clarity at at the expense of a sound that I’ve honestly come to greatly appreciate – the sound of the studio itself.

Over the years there have been some recording studios that have served not just as a place for instruments and vocals to be recorded, but also as an important and arguably essential element in the recording itself. The great Columbia 30th Street Studios come to mind, as well as the Van Gelder Studio, and for that matter Abbey Road and Trident Studios. These studios were not simply a location at which to record music but an important feature of the great recordings that were made in them.

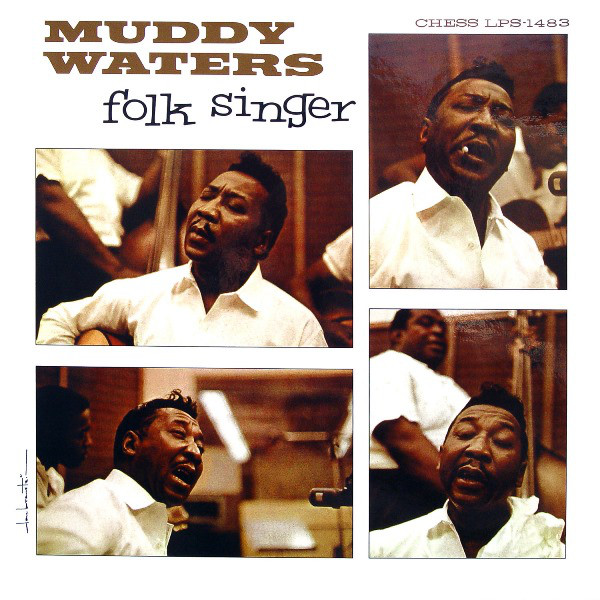

Not too long ago I was listening to my copy of Analogue Productions 2011 2 LP 45 rpm remastered reissue of what is probably my favorite Muddy Waters album, Folk Singer. This reissue, I thought at the time, has a lot to recommend it. It was clearly remastered from a stellar original tape as the sound is clean and clear and transparent. It’s also got a solid, weighty low end and plays dead quiet.

If I were your average audiophile collector I might have been content with AP’s reissue, but as I always am I was curious to hear a vintage copy and see if it might reveal some things about the sound of Folk Singer that were not immediately apparent on AP’s version. With original pressings rare and expensive, I opted for a 1970’s pressing, identified as a repress on Discogs and perhaps a 3rd or 4th pressing of the album.

Folk Singer was recorded at Chess’ Ter Mar Studios in Chicago as were a handful of his other Waters albums. Ter Mar also hosted several other blues and jazz artists in the 60’s and 70’s including Bo Didley, Howlin’ Wolf, Ramsey Lewis, The Dells and many others. I’m not sure if it would qualify as one of “the great” studios of its time, but if Folk Singer is any indication, it was clearly capable of producing some jaw dropping recordings.

It’s no accident that companies like Analogue Productions reissue records made from excellent recordings. I imagine that when audiophiles who buy AP’s records hear them they are more often than not impressed and for no other reason than the original recordings were just so damn good. When I first played their version of Folk Singer I was very impressed and honestly had a hard time imagining how the album could sound any better. But I persisted and learned some interesting things about this album, AP’s version and about the recording itself.

When I first played the 70’s repress of Folk Singer I was a bit disappointed. The record sounded good but the vinyl showed the residue of a poor quality plastic inner sleeve, even after a thorough cleaning, and it was very noisy. The first time I was able to sit down and give both the 70’s repress and AP’s version my full attention, I walked away thinking AP’s version had a clear edge, and because it played so quietly it was, in that respect alone, a much more pleasant record to listen to.

When I replaced my cartridge last year I noticed that records that had a ton of surface noise in the past were playing much quieter than I’d ever heard them. I hadn’t realized that my stylus was so worn before and that it was amplifying the surface noise on my records. I started revisiting some of my noisiest records and when I got around to my vintage copy of Folk Singer I was pleasantly surprised at how reasonably quiet it played with my new cartridge.

Considering also that this new cartridge, along with some very effective set up tweaks I’d made were yielding better and better sound from many of my records, I knew I had to revisit my two copies of Folk Singer and see if I still felt the same way about the AP reissue.

I want to mention here that I did take the time to adjust my arm height to account for the 200g vinyl the AP version is pressed on, and that the adjustment I made, I strongly believe, did bring out the best in the record. But the best this record can sound is still not enough to contend with what has turned out to be a very strong vintage copy in the 70’s pressing.

Why does the repress sound better? Two factors stand out to me. The first is a fully fleshed out midrange that gives the sound a body and depth that the AP version lacks. AP’s Folk Singer reminds me of their version of Pet Sounds in that way (written about here), the mids seem to have been drained off in order to draw the listeners attention to the higher frequencies and smooth out the sound. The guitars on AP’s version, for example sound clear and sharp, but they lack body and weight of real instruments.

The second factor that sets the vintage copy apart is the sound of Ter Mar Studio, clearly on display with this copy. The sound of the instruments and Muddy’s voice especially, are “living” in the studio space. When I got the VTA dialed in it was the sound of the studio space that especially impressed me. When I went back to AP’s version I realized that this sound was almost totally absent from it! In its place was the “black background” sound I’d been hearing on many of the modern records I’d played.

Veteran engineer Bernie Grundman remastered Folk Singer for Analogue Productions and he somehow managed to do away with the sound of the original recording and replace it with, what I might venture to say, is a modern audiophile’s idea of what Folk Singer should sound like. It’s not what I’d call a bad sound, but it’s by no means the same.

Muddy Waters, as he so often does, plays with such power and purpose on Folk Singer, and the vintage copy conveys his work with startling intimacy. The album was recorded in 1964 and presents as a kind of time capsule, offering the listener a chance to relive the moment he and his band laid down the original tape. Personally it is that moment in time that I’m interested in experiencing when I listen to Folk Singer, and to have it conveyed so convincingly is in my view what this audiophile hobby is all about.

I want to reiterate that AP’s version of Folk Singer is not a bad sounding record. It actually sounds pretty darn good. But it’s by no means the best version out there. Factor in that copies of AP’s 2 LP 45 rpm version have now gotten scarce and are creeping into 3 digit prices and you lose any remaining argument for forgoing a vintage copy for AP’s version.

If you’ve yet to add a copy of Folk Singer to your collection and you want to hear this incredible record as it was truly meant to be heard, you owe it to yourself to pick up a vintage copy. Just don’t sleep on it. Nearly every version out there is getting harder to come by and increasingly dear.