Recently a friend of mine offered to loan me a bunch of Moblie Fidelity reissues he had on hand. I’d heard a few of Mobile Fidelity’s records, or “MoFi’s” as they’re commonly known, and I was curious to hear more. After all, as heavy vinyl reissues go, MoFi’s are arguably the most consistently praised audiophile records among collectors, and until very recently they’ve been known for mastering all of their records from the original master tapes.

I’m certainly in favor of all analog mastering and remastering when the engineer has access to a good tape. All of the vintage pressings I favor were mastered from original tapes, or, based on the way they sound, at least a very early generation tape.

But there’s more to a great sounding record than an all analog mastering chain. Even if the mastering engineer has a good tape to work with, they still have to do something good with it.

Perhaps analog audiophiles and collectors these days are overly concerned with the source material and not concerned enough with the quality of the mastering, particularly when it comes to modern reissues. Case in point: the current controversy over Mobile Fidelity and the revelation that they have actually been using a digitization step in the mastering process on many of their records, and have been for some time.

I do understand why so many people are upset. We trust in the integrity of something we value and when we discover that our trust has been violated, we feel betrayed. Who among us has not had a similar experience and the same reaction to it? Deception is hurtful. None of us wants to be lied to.

On the other hand, the question that immediately arose for me when I heard this MoFi story was this – do their records sound any different now than before this SHOCKING revelation?

Now some might say, that’s not the point. The point is that Mobile Fidelity deliberately deceived their customers and still remains steadfast in their denial that they did anything wrong. Meanwhile, their customers want to know how they ACTUALLY made the records they’ve released over the past few years and that THOUSANDS of audiophiles and collectors have spent their hard earned money on. These folks want answers and, I suppose I’d have to agree, they’re entitled to them.

Nevertheless, I feel my question raises an important point, maybe THE most important point in this whole MoFi digitization business. Instead of feeling betrayed, why don’t we just listen to the records and let our ears decide if they’re worth the time and money they cost us? If we still like them then who cares if they’re not “pure” analog. Isn’t it the way the record SOUNDS that ultimately matters?

As I write this, I am listening to an interview on Youtube with Michael Fremer on the 45 RPM Audiophile channel on this topic. During the more than 45 minutes these fine gentlemen discuss this topic, there is extensive reference to another Youtube video that Mike Esposito of The ‘In’ Groove, the man who uncovered this MoFi digitization story, made to document his trip, on his own dime mind you, from his record store in Arizona to Sebastopol, CA where he talked for nearly and hour with the folks at Mobile Fidelity about their mastering practices.

There are also quite a few more videos, AND forum threads, all commenting on these videos and this controversy in general, including this article, collectively tallying up to a great number of hours spent beating the dead horse that is this topic. Hours that could have been spent playing these records and making up our own minds about whether this digitization thing really even matters. Digital or no Digital, if you like ’em you like ’em and if you don’t you don’t.

I’m afraid that when it comes to MoFi’s records, at least the ones I’ve heard, I’m squarely in the latter camp. They have a sound that a lot of people like and that I find bordering on insufferable. To my ears, MoFi’s records have an uncanny way of grabbing my attention and making an appealing first impression, only to reveal themselves upon relatively little further listening as sorely lacking in naturalness and musicality. The longer I play them the less I like them and the more annoying they get.

As I went through this pile of MoFi’s I wasn’t thinking about how each of the records was mastered. I wasn’t thinking about analog or digital. It never even crossed my mind. What I was thinking about was whether any of these records had something to offer me as a listener, a listener who already has a rather substantial pile of excellent sounding records to play. Records that actually sound BETTER every time I play them.

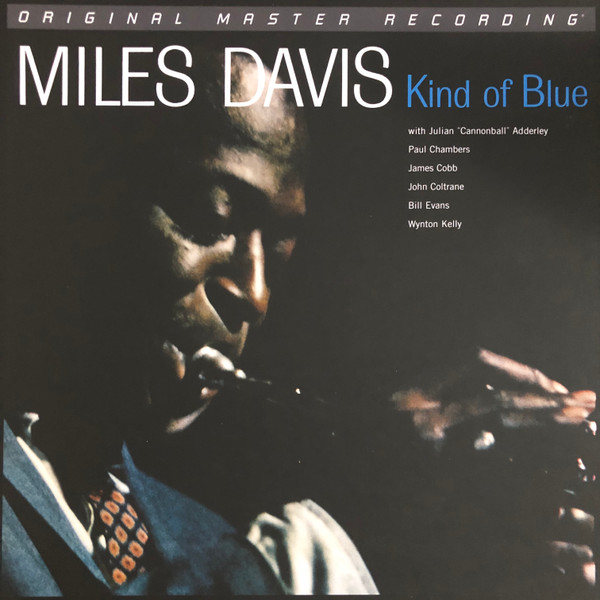

At the top of this pile of MoFi’s was a repress of their 2015 reissue of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, released again in 2020. Miles Davis’s masterpiece is a record I happen to own a very good copy of and it’s a record I’ve spent a fair bit of time with. I also wrote about it here not too long ago. Of all the jazz records you could name, I’d venture to say this is one that I have a better idea than most of how it can and should sound.

My impressions? From the very first note on this MoFi I could hear the bass was boosted, and overall the record sounded bloated, fuzzy and tonally wrong. Adderley’s sax sounded shrill and edgy and Coltrane’s squawky and oddly distant. Paul Chamber’s bass was boomy and flaccid and Cobb’s drums and Evan’s piano both lacked solidity and impact. The best thing on the record is Miles’s trumpet, although the best thing I can say about that is that it’s less shrill than the other horns.

Even worse than all of the above is an odd sense I had listening to MoFi’s KOB that somehow the proportions of everything on the record were off. There’s a lack of cohesiveness and the musicians don’t seem to be playing together, but rather sound like their parts have been cut and pasted into the soundstage.

No amount of fiddling with my VTA yielded anything than marginally better results. The problem wasn’t the arm height. The problem was the way that Mobile Fidelity recut this record.

I’d call this MoFi the Frankenstein’s monster of KOB. It’s got all the right parts in all the right places but remains an unconvincing, monstrous representation of the album. Not once listening to it did I feel even remotely drawn into the performance. Instead I found myself frighteningly confused and wondering how it had gone so terribly wrong.

Was this record done all analog? Maybe. Supposedly Mobile Fidelity has been incorporating this digitization step since 2016, and this record was mastered back in 2011. Perhaps this is one MoFi that was in fact, as stated on the packaging, “Mastered From The Original Analog Tapes.”

Does it really matter? Not to this audiophile. And I hope more audiophiles will realize this as well – just because a record SEEMS to have the right pedigree, doesn’t necessarily mean it will deliver the goods on your turntable. In fact, my experience has taught me that when it comes to Mobile Fidelity’s records, “Mastered From The Original Analog Tapes” means very little in terms of how they sound.

If you own this MoFi and you’re happy with it, don’t take offense. Just consider my words, and if having done such, you still feel doubts about your own judgment, consider this. Maybe you just haven’t heard HOW GOOD Kind of Blue can actually sound? Maybe, just maybe, you still have room to grow in analog audio. And after all, isn’t that a good thing?