If you spend enough time playing record after record and tweaking your system the way I do, eventually you come back to a record you’d used as a reference disc in the past and realize it was not a very good one in the first place. Perhaps it’s because of my compulsion to not only seek truth in audio, but to actually reach it now and again, that I keep declaring records to be the be all and end all, only to realize later that maybe I should have stuck with my Hot Stampers.

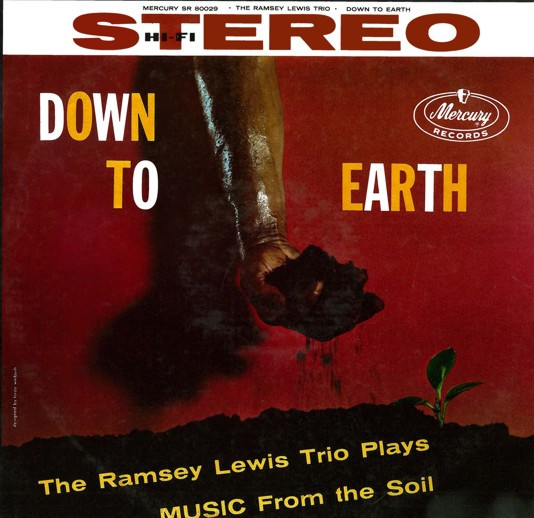

Nevertheless, I do manage to find a record occasionally that shows me something special now and holds up to further scrutiny later. When I first heard The Ramsey Lewis Trio’s Down to Earth (Music From The Soil), I knew right away I was hearing something special. Three musicians packed into a small but venerable Chicago recording studio, swinging like crazy and playing the daylights out of their instruments is not something you can hear once and easily forget about.

And since hearing it, I’ve been obsessed with Down to Earth. Yet I’ve found listening to the album more often confounding than satisfying. Generally this kind of small jazz group recording is what I would call the “low hanging fruit” of audiophile listening. Three musicians playing in a studio will often make for a relatively uncomplicated, fairly easy to reproduce record. But as I soon discovered, this was a more challenging record to play than I’d originally thought.

It is, however, a great recording. And part of what makes it great is the very thing that makes Down To Earth challenging to play. The musicians are in close quarters here, and they’re playing very close to the microphones. When the trio plays softly, the sound is exquisitely intimate and startlingly immediate. As they play a little louder, the intense clarity of the percussion and the fluid, propulsive rhythm of the music sound wonderfully alive.

But when these three gentleman begin to play louder, when they break out the fire that infuses this album, especially Lewis, then there is literally nowhere for us to hide from the intensity of this performance. If at that point the music doesn’t hold up the way it undoubtedly would at a live venue, then either we’ll have to grit our teeth and bear it or turn down the volume.

Take the song “Soul Mist.” It starts off easily enough, opening with some light, airy brush strokes and the gentle tinkling of bells. Red Holt taps his drums softly, and Lewis’s soulful piano eases us into the melody. Then the cymbals get a little bit louder and we can start to feel the weight of Lewis’s piano and the firm woody pluck of El Dee Young’s bass.

Suddenly, about halfway through the song, Lewis gets a little heavier on his keys, and then WHAM! He starts to really wallop them. At that moment, if your system is not ready, forget about liking the sound of this record. You may be loving every second of it until then, but when that moment comes, if your system and / or your room isn’t ready for it, you’ll be reaching for the volume knob.

Down To Earth will challenge any system playing it back, but the right system can, indeed, play it back, and play it in way that is both pleasing and eminently satisfying. Lewis spends a good chunk of this album POUNDING the bejeezus out of his keys, and to fully appreciate the power of his performance, and still experience the magic of the album’s quieter moments, the record needs to be played at a live volume, and the piano needs to sound right.

If you want to hear a record that DEMANDS neutrality from your system, look no further than Down To Earth. Even the slightest peak across the frequency spectrum will stick out like the sorest thumb. But when you get it right, the payoff is a realism and musicality that will leave you dreaming about the record long after you’ve lifted the needle. You may even realize, as I have, that the parts of the record that already sounded pretty darn good could still sound better.

This recording has the kind of top end that would make anyone at Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs green with envy. The drums, cymbals and bells resolve so beautifully and with the kind of substance and airiness that we typically only hear at a live performance. My system had been getting the percussion pretty right, but the piano was giving me problems. Then when I finally got the piano to sound right, and at the right volume, I heard something that thrilled and surprised me.

On “John Henry,” when Lewis comes into the song about 45 seconds along, drummer Red Holt starts to hit his cymbals with such an intense thwack! You’ll wish you hadn’t just had your ears cleaned. I had heard those cymbals sounding pretty right before, but what I heard this time was the sound of the drum stick hitting the cymbal itself. I heard the moment of contact, just before the cymbal starts to shimmer. It happened only a microsecond before the sound became music, when it was still just the sound of a hard wooden stick hitting a thin metal disc.

It occurred to me then that Down To Earth is far more than a jazz album. It’s a recording that features the most basic elements of sound itself, and of the people making it. Music From The Soil, as the title says, is of the earth, but it’s also got more than your fair share of fire and water, air and ether, wood and metal, blood and bone. Down To Earth is an album featuring the most basic elements of our physical world, realized in the form of a jazz record. And if that’s not something that’s worth building a better stereo to play, I don’t know what is.