I consider myself a jazz fan, but not an educated one. I’ve been fumbling along for years buying various jazz records, enjoying many of them but loving very few. Perhaps it’s because I’m not a musician myself that I haven’t fallen in love with more jazz recordings. I can appreciate what is clearly stunning musicianship on many of these records, but since I don’t play myself and I don’t understand music theory, I often feel I’m appreciating only a fraction of all that’s going on.

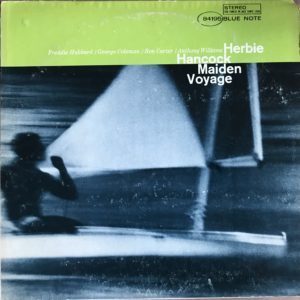

But as they say, I know what I like, and occasionally I connect with a piece of jazz music on the aesthetic and emotional levels that I approach all music on, and when I connect this way with a record it can come to be true favorite. Such is the case with Herbie Hancock’s fifth album, Maiden Voyage.

Maiden Voyage is a concept album inspired by the sea and it’s many mysteries. It’s meant to capture and convey the experience of a ship at sea for the first time and the experiences of its passengers. My understanding of jazz music may be limited, but I understand enough to know that recording a piece of music like Maiden Voyage requires every musician involved to be 100% on board. It turns out that an early recording session for Maiden Voyage with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard playing coronet and Stu Marin on drums in place of Anthony Williams did not capture the magic Herbie was seeking, and the recording of that session was scrapped for the one that ultimately became the final version. That version, with Freddie back on the trumpet, Williams drumming, Ron Carter on bass and George Coleman on the tenor sax is perfection! The playing is so well navigated that the listener is never given a chance to abandon ship.

I was given my first copy of Maiden Voyage by a friend who bought a lot of records but played them very little. That copy is a 1985 DMM reissue in near perfect condition. As I began listening to the record, I began to see I was in good hands with these musicians and gradually, I started to sit back and let the music carry me away. For a while it was blissful! If I wanted to wind down after work, or relax on a lazy Sunday, I would put on Maiden Voyage and be transported. That is, for a while…

When I fall for a record, it’s only a matter of time before the audiophile in me rears his ugly head and starts noticing it’s shortcomings. I started to hear some things on the DMM copy that I wasn’t sure I really liked. I decided to buy a different copy and see if I could learn something more about what sonic qualities best served this seminal work of art.

My research into pressings has informed me that 70’s jazz reissues can be terrific buys for 50’s and 60’s recordings. Typically these reissues are relatively inexpensive and the mastering quality is often extremely high. Vinyl quality is an issue, but it’s easier to find them in good condition and the sonics can be flat out magic. I found a good deal on a 1973 reissue of Maiden Voyage mastered by Bert Agudelo in pretty good shape and bought it. Now I was ready to see if these two copies could help me dial in the sound that would liberate me from listening critically to Maiden Voyage so I could go back to simply being transported by the music.

Before writing this, I felt I needed to understand better what DMM or Direct Metal Mastering was all about. If you’re not already familiar with DMM it involves cutting the master stamp – that which will be used to press the vinyl, directly onto a copper plate. On a record mastered in the “conventional” way, the master stamp is cut into acetate lacquer on an aluminum plate.

DMM promises to deliver several distinct advantages over conventional mastering. First, the much harder metal surface material used in DMM is not prone to the groove wall bounce back effects that the softer lacquer surface is, and therefore grooves cut into the harder metal surface have the potential to more accurately represent the modulations of the master recording on the stamper as well as on the vinyl and ultimately in playback.

Second, because conventional stampers, are made from a “Mother” which is a second generation master made from a “Father” which is the first generation master that was cut with the lathe, pressing with these conventional stampers amounts to using a 3rd generation stamper for pressing the actual records. DMM records can be pressed from the “Father” or first generation stamper and therefore the DMM process eliminates 2 generations of stampers from the production chain and 2 opportunities for diminished accuracy and increased noise in the final product.

Third, the DMM process not only reduces noise and produces records that play quieter, it also produces records that play with more upper frequency levels than conventionally mastered records. Okay so, records that play quiet and reproduce our favorite music with more highs, less distortion and optimal accuracy, what’s not to like! I mean, shouldn’t all of our records be made with the DMM process? And why in God’s name are they not?

One reason is that there are just not many DMM mastering houses left. There are only 6 or 7 in Europe and none in the US. Currently there are not enough mastering and pressing operations in the world of ANY kind to keep up with the growing demand for vinyl, let alone DMM facilities.

But it also turns out that, sonically, DMM may not always deliver on its promises. DMM records have a reputation for being “bright” or “edgy.” Some people find the tonality of DMM records to be off, and some listeners find them harsh in the high frequency range. I’d weigh in here and say that anyone who has ever listened critically to records knows that when it comes to the upper frequency range, more is not always better.

My experience with the DMM copy of Maiden Voyage was mixed. It plays dead quiet and often plays with a “CD like” clarity that translates into terrific leading transient edges in the horns and good depth in the soundstage. But just like the majority of conventionally mastered records, it is still prone to distortion, and ironically this copy sometimes fails to resolve well at all of the frequency ranges, including the higher range. As a listener I find this distortion very distracting and that it interferes a lot with enjoying the music.

So it appears that DMM doesn’t eliminate the pressing issues that cause a record to distort, even if, perhaps, it may reduce these tendencies. I haven’t listened to a large enough sample size of DMM mastered records to know if these records are any less prone to pressing flaws than conventional ones, but clearly they do have them. Therefore buying a DMM record will not guarantee the kind of top end resolution that gives a record the ambiance and sense of studio space that in my mind really separates the decent sounding records from the truly great.

Now don’t get me wrong, the DMM pressing of Maiden Voyage is a good sounding record. I have been shifting back and forth between this and the 1973 reissue A LOT to decide where my preferences really lie. But ultimately I’ve come to the conclusion that this album deserves better than the DMM copy gives it. This may not be true for all copies of this DMM version, but I’m convinced it’s true for this one.

So how does this ’73 reissue stack up? I’d say that the copy I bought succeeds in delivering much of what I’ve come to understand jazz records mastered in the 70’s can deliver. For one, the tonality is spot on. This alone makes the record a great deal more listenable than the DMM version. Correct tonality is important with all instruments, but nowhere is it more essential than with horns, especially trumpets. When it’s right, trumpets sound sweet, breathy and clear. When the tonality is wrong, trumpets can sound edgy and irritating. I wouldn’t say the DMM fails totally with Freddie’s trumpet or I’d never have been able to keep listening long enough to fall in love with the music, but the ’73 reissue improves on it significantly.

Another interesting difference between these 2 records is the extent to which each conveys studio ambience. One might think that a record that plays quieter and delivers more at the top of the frequency range would convey studio ambience superbly, but it turns out in this case that’s only partly true. On the DMM copy the higher frequency range often comes across as too forward and lacking the sense of space around the instruments that is the hallmark of studio ambience. On the other hand, it does play quiet and the ’73 reissue does not. Therefore it wasn’t until I could get some extended man cave time alone with the ’73 version and really turn up the volume that I could appreciate that it did indeed covey much more of the studio ambience than the DMM, albeit with some surface noise in the background as well.

It’s interesting to me that at that higher frequency range where the DMM is really supposed to deliver big, it sort of just sounds louder. Meanwhile the highs on the ’73 version are every bit as clear and present, but they live in the studio space and don’t scream for attention at the front of the soundstage. Again, this translates directly into making the ’73 version more listenable and engaging. When Freddie and saxophonist George Coleman are playing together, the trumpet plays mostly from the left speaker and the sax mostly from the right, but the ’73 has them playing together on opposite sides of the studio while the DMM has them playing just out of the left and right speakers.

One of my favorite elements of Maiden Voyage is found in Anthony Williams’ drumming. His use of the symbols conveys so beautifully images of waves crashing and wind lashing at the sail. A sense of space around the symbols is essential to conveying these images and the feelings they evoke. The ’73 reissue manages this beautifully, the DMM version not as well.

And of course there is Herbie’s piano. I find this instrument, perhaps more than any other, sounds false on most records. A piano that sounds false sounds like it’s all keys and no body. The key strokes can sound bright and lacking in weight. Thankfully that’s not the case with this ’73 reissue. The instrument is fully present, tonally on and weighty enough to convey the steady listing of a ship at sea.

There are many more versions of Maiden Voyage in the used market to choose from than those I’ve discussed here. These include a rather large number of ’70’s reissues at affordable prices. The earliest pressings, like many classic jazz recordings, are rare and expensive in good condition. Outside of the collectability of factor of these pressings, I doubt you’re better off spending 3 figures to get one, given the quality I’ve experienced in this ’73 reissue. I think also that for a collector with a more modest system, the DMM version is still a good option, especially if it’s played more often at lower volumes.

But for the majority of audiophile collectors I would not recommend a DMM mastered version of Maiden Voyage. The music, performances and recording deserve better.