by TBR contributor ab_ba

When you hear a good record played on a good stereo, it’s a marvel. When you hear a GREAT record played on a GREAT stereo, it can be BREATHTAKING. I think this is why our hobby has so many pockets of complacency. Once you get past a certain point with your gear, and once you’ve made a commitment to a type of record that you feel is working for you, everything’s sounding really good to you, and you can’t imagine it getting any better.

But I can almost guarantee you, your stereo has shortcomings. How do I know this? How can anyone know it? Go listen to a TRULY great stereo. Find one that’s doing EVERYTHING right, and you’ll just say, “Oh.”

I had precisely this experience last week when I went to visit Robert, host of The Broken Record, in his home, and we spent a wonderful day sitting in the presence of his remarkable stereo. I’ve been an avid reader of his blog for a couple of years now, even contributing a post of my own. I was intrigued by the journey Robert was on, and I wanted to learn more from him, and do my best to follow him on it.

A couple years ago, Robert and I struck up an online conversation, and we began mailing each other some particularly great pressings of our favorite records. So when I knew I’d be in his neck of the woods this month, I offered to bring over my stack of White Hot Stampers and a good bottle of Italian wine. Robert took the bait, and we had a lovely time meeting in person. I wish we could all do this type of thing more often – spend time in each others’ homes, sharing favorite records, and getting to know each other as real, three-dimensional people, and not just as voices on the internet. But I digress. What I really want to do now is to tell you about Robert’s stereo.

Like me, Robert has followed the path Tom Port laid out for us: the Dynavector Karat 17dx cartridge, a Tri-Planar tonearm, the E.A.R. 324 phono stage, a low-powered solid-state amp driving high-sensitivity speakers (Legacy Signature iii’s for us both). Robert’s even got his speaker wires dangling from the ceiling, just like Tom does, as you can see in the photos from Geoff Edgers’ Washington Post article. I could almost hear Tom saying approvingly, “there’s no hifi without that piece of string”.

I want to try to describe for you what the experience of hearing a truly great stereo, with well-curated gear, in a properly configured room, and with a stack of great records to play, can sound like. Of course, you’ve ultimately got to hear it for yourself, but I’ll do my best to convey my experience.

First, there is a remarkable lack of distortion. It’s hard to convey the significance of this without hearing it, but I can promise you this: your stereo has distortion. Even after you’ve dialed in your cartridge, even after you’ve conditioned your power, even after you think all the flaws have been fixed, you’ve STILL got distortion. Because it’s only when it’s gone do you realize it’s been there the whole time.

Where is that distortion lurking? It’s in the obvious places, like a pressing of a record that’s opaque or with smeared out details. It’s in a VTA setting that isn’t dialed in yet for that particular record, or in a fancy cable that has an attention-grabbing sonic signature, but is imparting that signature to everything you play, like a cool filter effect on your phone’s camera.

That distortion is also in the subtler places, like a preamp that isn’t mechanically isolated from its shelf, or a room mode that hasn’t been damped. It’s only when you are hearing a system where all of those subtle sources of distortion have been addressed that you realize you’ve been hearing them all the time in your system, but just not realizing it.

What do you get when you contend with and remove distortion? Backgrounds you thought were black, get even blacker. Sonic images click into focus, with each instrument occupying its own place in the soundstage, and when you hadn’t even realized the imaging had been indistinct. The space around the instruments becomes palpable. You can hear the studio in which the band was playing. You may even think your stereo already has these attributes of resolution and focus; I thought mine did. But, now I know I can go further, and I can’t wait to get started.

So, if we can’t hear distortion until it’s been removed, reason leads us to conclude that we can never declare a stereo free of distortion, even one that sure sounds like it is. And indeed, Robert could readily demonstrate for me that his system still has some distortion. While I sat there marveling at the sound of John Bonham’s drumming on his pristine Ludwig pressing of Led Zeppelin 2, Robert hopped up to shut off the breaker to the fridge.

The improvement in the sound was evident, even when I was just thinking none was possible. The background was even blacker, with even more delicacy revealed in John’s fingers on the hand drum. I can only extrapolate from this that even Robert’s got more distortion he can be rooting out in his system. I look forward to visiting him again and behold whatever further progress he might have made by then.

The second thing a truly great stereo can give you is soundstage depth. I find that this is the most instantly impressive aspect of great stereos. Most good stereos convey some sense of depth. I’ve heard speakers that sound more forward-leaning, and others that are more laid-back, but truly great audio is when the speakers create a deep sound stage, with some musicians clearly in the front like a horn player or the singer, and with the bassist or backing vocalists clearly deep in the soundstage, but still quite audible. The effect is beguiling. With eyes closed, it’s immersive. With eyes open, it’s astonishing.”

The experience of soundstage depth on Robert’s stereo reminded me of my previous best stereo I’d ever heard – Todd The Vinyl Junkie’s amazing Vivid Giya speakers driven by Luxman monoblock amplifiers, his gigantic VPI turntable sitting between them and spinning sweet, sweet vinyl. I’ll never forget the way Stevie Nicks was so palpably in front of me on the Steve Hoffman pressing of Rumours that Todd played for me. I’ve longed to have an experience like that again, and sitting with Robert listening to a vintage copy of Oliver Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth, it happened again. Now I have a new goal for my own listening room – true soundstage depth. And it’s thrilling to know I don’t need to buy a $200,000 stereo like Todd’s to experience that.

The third thing you learn when you hear a truly great stereo is how different two similar records can sound. I mean, we all say it, but a good stereo makes those differences rather stark. I brought along my White Hot Stamper of Aja. We played it next to the best of the many copies Robert has found on his own over many years. His copy sounded great, of course, but we both agreed mine was cleaner, more detailed, and more dynamic. Just by a little bit, mind you, but all those tiny bits add up to a meaningfully richer experience.

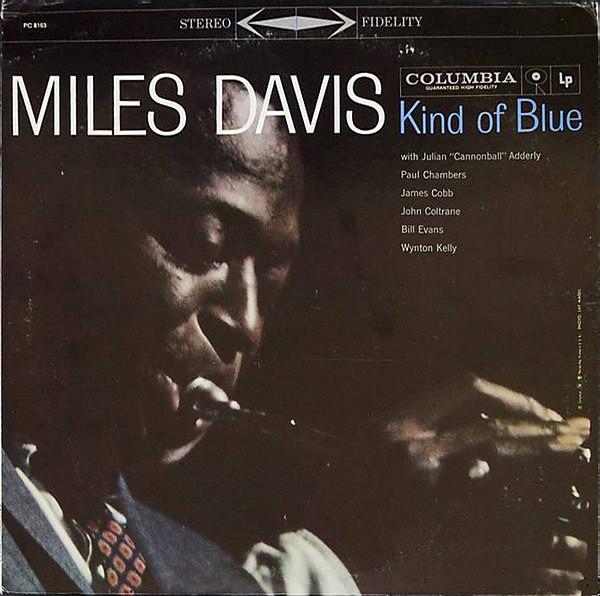

We played my UHQR pressing of Kind of Blue up against the best copy of that wonderful record that Robert’s been able to find on his own. The UHQR simply fails to do justice to the music. I thought it sounded pretty good on my stereo, but luckily for me, Robert had a close-second copy (same matrix, but a less-great pressing) set aside for me.

Before dropping by Robert’s place, I had visited a local shop he recommended, and there I came across a sealed John Coltrane Prestige twofer (ssshhhh… don’t tell anybody… these Prestige twofers can be AMAZING.) Robert looked at it and said, “I have a few of those. You’d have to get really lucky to have gotten one with the right stamper.” As we opened it up, I was feeling like I was ten years old again, opening up a pack of baseball cards. Sure enough, my stamper matched his best copy!

We listened to them both, and man did they sound different. Robert, ever the gentleman, handed my copy back to me, smiled, and reassured me, “it’ll sound better once you clean it.” But, it takes a system like Robert’s to hear these differences between records. Listening to good records on a good system is a delight, but hearing a great system is an absolute revelation. If you want to find really great copies of your favorite records, they’re out there, but you need a stereo that will enable you to identify them.

There’s this feeling of peace I get when music is playing. It doesn’t matter if it’s “Blue in Green” or “Baba O’Riley”, music focuses my mind and anchors me in the moment. I can sometimes get to that place in other ways – if I dedicate my energies in yoga, meditation or exercise, or when I get engrossed in a movie, a book or a conversation. But music takes me to that place faster and more consistently than anything else. Music reproduced well takes me even further, and deeper. Again and again yesterday, I found myself at peace, absorbed in the experience of just listening, sitting in the sweet spot between the speakers with a good friend right next to me.

Robert’s system, like mine, is cobbled together from vintage gear, some of it refurbished. Also like me, he’s cycled through a bevy of higher-priced more-mainstream gear over the years. You know, the type of stuff you’ll find advertised in the trade magazines, and hear in showrooms and at audio shows. I love that that industry exists, but if you want to hear records sound the best they can, if you want the truest reproduction of what’s on the vinyl, new gear and modern re-pressings are simply not going to get you where you want to go.

But, the only way to know this is to take the plunge, try it out and hear for yourself what’s hidden in the dusty grooves on a vintage record, played on a stereo designed to play them. And who knows, you may even make a few new friends along the way.