I’ve written quite a few articles highlighting the importance mastering plays in the sound of our records. The mastering engineer, as well as the equipment they use to do the mastering, can literally make or break the sound of a record. It is a key part of us hearing the work of the recording artist the way it was meant to be heard, and a big reason why so many modern remastered records fall so terribly short.

Aside from the mastering, our playback has an absolutely MASSIVE role to play in the sound of our records, and the music on them. In fact, as obvious as this might seem, I’ve found playback to have an even bigger role than most of us realize.

I’ve just gone through a rather lengthy turntable change in which I moved my Triplanar tonearm to a different table. Almost immediately, I started testing platter mats of different thicknesses, which means I was making a lot of changes to the arm height. At best, I’d say I was getting only a close approximation of the correct arm height during each of my tests.

Which raises the question – were the changes I was hearing due to the differences in the platter mats, the arm heights, or both? Ultimately I concluded that, regardless of these uncertainties, one combination of platter mats sounded convincingly the best. So I decided to move forward with this combination and began working on the other elements of my setup.

At this point, I was still adjusting the arm height entirely by eye and by ear. Playing record after record, knowing that with each one the arm was a bit too high, I reduced the arm height a little each time to see how it impacted the sound.

This, by the way, is absolutely NOT the way to adjust your arm height. Make the arm parallel to the record surface and then, if you’re so inclined, make tiny adjustments up or down to improve clarity and tonal accuracy.

Still, hearing some of my favorite records played with the tonearm at different heights was pretty interesting! With a few of these records, there were moments where I could’ve sworn I’d never heard THAT record sound THAT good.

On Julie Is Her Name, for instance, there was a point where Julie’s voice opened up so dramatically and with such wonderful presence, it took my breath away. As far as I knew then, at that moment, that was the perfect height for my tonearm.

Nevertheless, I didn’t stop lowering the arm, and soon I realized that that was not, in fact, the perfect height for my tonearm. Not if I wanted every record in my collection to sound its best.

When I finally did get the arm to the correct height, I went back and played some of the records that had sounded AMAZING during this exercise, only to discover that, while these records still sounded wonderful, the elements of the music that had JUMPED out to me before had settled back into a less dramatic, more balanced and ultimately more accurate representation of the recording.

A few years ago, Better Records founder Tom Port told me something that I’ve never forgotten. I had just demoed my system for an industry guy, and while relaying the experience to Tom, he asked me what records I had played for him. I mentioned a few, including Charles Mingus‘s Ah Um.

Tom said (paraphrasing here) “Not a good choice. You want to play records that can only sound good one way. Ah Um can sound good a lot of different ways.”

At the time I didn’t fully understand what Tom was getting at. Ah Um, or at least the copy of it I had, always sounded great. Wasn’t it therefore a great record to demo my system with?

Since then I’ve come to understand that this was exactly Tom’s point. If you really want to show someone what your system can do, by all means, play a great sounding record, but also one that requires your turntable and your system as a whole be at their best to reproduce it.

Lately I’ve come to understand something that I feel every audiophile, analog audiophiles in particular, would do well to recognize and come to terms with. When we play a record, each of us is listening for different things, and these things are very often not the things that we should be listening for if we want to determine if our system is sounding its best.

When I got my very first pair of floorstanding speakers, I had spent decades with the same pair of “bookshelf” speakers. Finally, with these bigger speakers, I could hear a drum kit sound more like a real drum kit. For a long while thereafter, I was laser focused on the sound of drums on every record I played. During that time, any record or system change I was inclined to like was one that highlighted the sound of that instrument.

Of course there’s a lot more to a recording than how the drums sound. If we’re focused on that instrument, or on another one perhaps, or on how much bass there is, or how resolving the top end is, or even how transparent the sound is, typically we do this at the expense of some other elements in the music. Transparency, for example, often comes at the expenses of weight.

But when our stereo does just some things well and other things not so well, we’ll only want to play the records that sound good on our system and will avoid playing the ones that don’t.

To some, this might seem a reasonable compromise. After all, there’s only so many hours in the day. How many records can we really listen to anyway? Maybe there’s an advantage to having the list of agreeable options whittled down.

Personally I find hearing a record that ought to sound good not sound good really annoying, to say the least. Why the heck doesn’t it sound good? This gets under my skin in the worst kind of way.

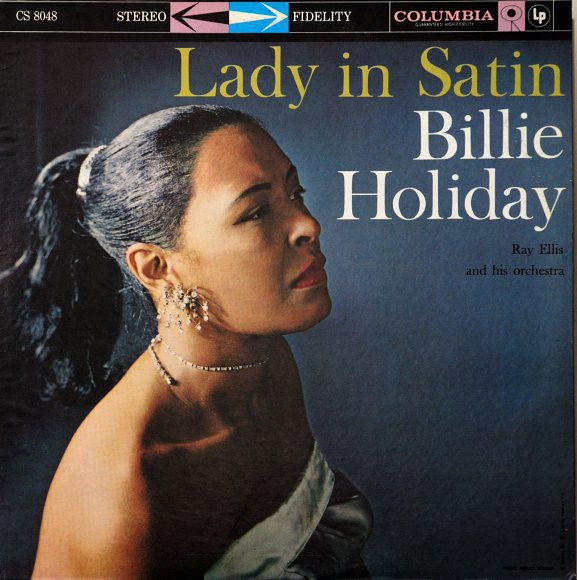

During this tonearm / platter mat exercise, I was having this very experience with one particular record, a copy of Billie Holiday’s Lady In Satin. I was fairly sure this copy was a winner. It was a version I knew had been mastered well, and from a good tape. It had also sounded very good to me in the past.

But as I played the record at different stages of my setup, it just wasn’t sounding the way I remembered. Maybe I had misremembered? Wouldn’t be the first time. Or the last.

The problems centered mainly around the vocals. Billie’s voice was not at its peak when she recorded this album, and on the best copies you can hear its frailty, peeking out from behind her still formidable phrasing.

In this case, before I had the tonearm set right, Billie just sounded . . . old. And dare I say, feeble? This new turntable is more revealing than my last one. “Maybe,” I thought, “I’m just hearing more on this recording than I’d been able to in the past.” Maybe this was how the record was supposed to sound.

And yet, it clearly wasn’t musical, and that convinced me that either this copy was a mere shadow of the one I thought I had, or I just wasn’t playing it right.

It turned out to be the latter. Once I got the arm set right, the record came to life beautifully! Billie sounded big and warm and both wonderfully musical and heartbreakingly vulnerable, a combination so fitting for the love songs that compose this special album.

If you’re familiar with Lady In Satin, you already know it is a record that deserves a place alongside some of the greatest jazz vocal records ever made. In its own way, it might even share some of the same rarified air that Ah Um does.

But a pretty steady diet of Ah Um for a number of years now has taught me that the right copy will sound good, even with the most basic turntable setup, and even on a system that’s not performing its best.

Meanwhile, it would seem that Lady In Satin is a record that only sounds good, great even, one way and one way only. It needs us to attend to all the little details in our system before it will reveal its magic.

Lady In Satin is not alone in this regard. It is just one among a great many records that not only deserve to be heard, but to be heard right. These records need both great mastering, and masterful playback. They demand the right equipment, set up in just the right way. And only when these records are played back right will the music on them engage us, captivate us even, as only these records can.

As I see it, playing records like these and playing them the right way is what analog audio is all about. And even though analog presents seemingly endless challenges, all the time and effort we put into meeting those challenges pays off when we can play a record like Lady In Satin and truly appreciate how great it is.