by TBR contributor Alex Bunardzic

Once upon a time it seemed that western music was changing as frequently as the seasons. A highly fertile period for music happened in the span of just 10 years, between 1965 and 1975. It came as an explosion in musical innovation that started with the Beatles, among the first to experiment with the sitar and other unconventional musical instruments in their recordings. Soon after other talented musicians followed their lead, and by the end of 1960’s mainstream music was well on its way to becoming a formidable transformative force in modern society.

The tireless pace of experimentation and change during this decade in music had also affected leading jazz musicians, including Miles Davis. Miles started experimenting with jazz forms in 1965 with the formation of his second great quintet, and it wasn’t long before the influenced of popular musicians of the time including Jimi Hendrix and James Brown were influencing his music. By 1968 Miles started experimenting with electric instruments and began adding unconventional instruments into the mix. The sitar, tabla, bass clarinet, exotic percussion instruments and distorted electric guitars and keyboards became staples of Miles’s music by the late 60’s.

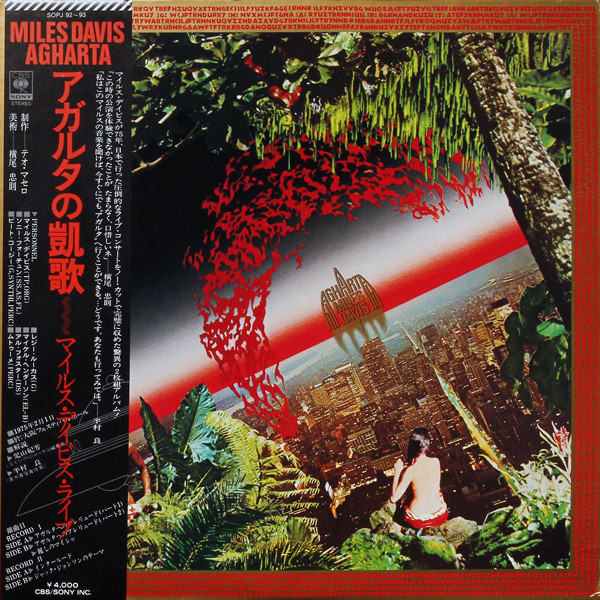

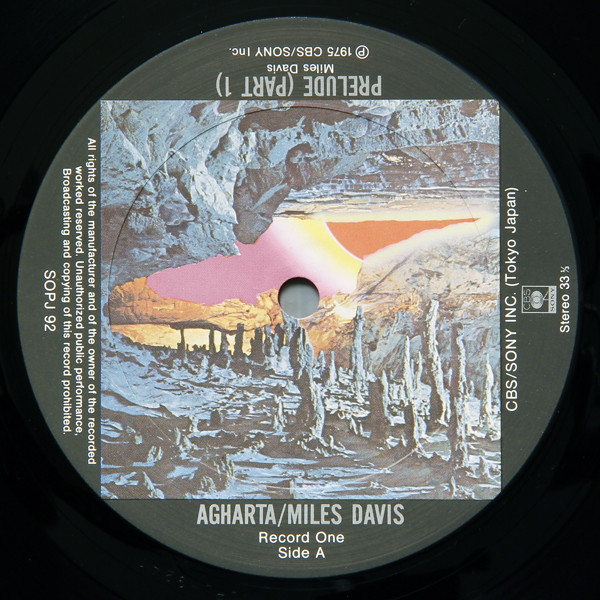

The ensuing 6 years (from 1969 to 1975) saw Miles relentlessly changing his music at a pace of change that was almost maniacal, and this resulted in one of the most fascinating bodies of work ever recorded. The culmination of this period of restlessness and experimentation came on February 1, 1975 in Osaka, Japan. On this day Miles and his band played two sets, one in the afternoon and the one in the evening, and both performances were recorded for posterity. The first concert became the double LP Agharta, and the second was issued as the double LP called Pangaea.

This article will focus on the former of these, Agharta.

There are several variants of this seminal album available on the market today. Originally issued in Japan, Agharta was subsequently released in the US, in the UK and in the Netherlands. It wasn’t until 1991 that this album was digitized and issued as a double CD by Columbia.

Since then, there have been a few attempts to revisit this album with just a small handful of reissues and remastered versions. A Japanese DSD remaster was issued in 2009, but no vinyl reissues were released until 2011 when the boutique vinyl house 4 Men With Beards published a brand new pressing of Agharta in an attempt to fill the vacuum on the vinyl market. Then in 2015 another boutique vinyl house, Music on Vinyl, followed suit with their own reissue.

The Historical Significance Of Agharta

The Beatles helped spark a musical revolution in the 1960s that brought a rejuvenation of social energy, mobilizing the younger generation to embrace radical social change. But it didn’t take long for the band’s initial enthusiasm for change to sour. By the Summer of Love in 1967 The Beatles had turned from a powerhouse of exuberant youthful positive energy into a world weary destructive force.

“A Day In The Life” from Seargent Peppers seems to signify the end of western popular music as we know it. The song’s railing chaotic crescendo near its end, followed by a crushing chord played by four grand pianos serves as this signal. Shortly after, The Beatles followed this ‘mercy killing’ of music, hammering the last nail in the coffin, as it were, when they released the amazing and mind boggling “Revolution 9” on their epic White Album.

Around this same time, Miles Davis carved his own path of musical destruction by performing a kind of parallel exorcism in the area of jazz music. He dismantled the traditional notion of jazz by melding it with rock, funk, soul and experimental avant-garde music. Miles was the most prominent figure head in the world of jazz at the time, and his abrupt move in this direction left many followers reeling with bewilderment.

In 1975 Miles completed his symbolic dismantling and burying of jazz music when he released Agharta. This stunning album stands as a milestone and an essential landmark for the end of this fertile period of experimentation and innovation in mainstream music. And while experimentation in music certainly continued after Miles’s retirement in 1975, it hasn’t since reached the same level of mainstream awareness as it did with Miles at the helm.

As we look back today, we can see that this pivotal decade ended not only with the destruction of experimental music, but also ended many other progressive movements in society. Film, theater, visual art, philosophy, literature, all of these essential areas of human creativity began turning away from experimentation and toward the mainstream, in the process becoming increasingly commoditized. Art started turning into a brand and a marketing campaign, valued only by the number of dollars that it could generate.

In music, sadly, it doesn’t seem possible to expect another accomplishment as epic, even titanic, or one that would be at the same cosmic level as Agharta. Fortunately we can buy a copy of Agharta and continue to celebrate Miles’ work and his outsized contribution to music.

The Various Editions Of Agharta

My first exposure to Agharta was with the Columbia Jazz Contemporary Masters label (released in 1991 on double CD). It was a fascinating encounter, and after reading up on the historical details surrounding this album I came to understand that the mixing and the mastering of the CDs resulted in a markedly different sound than that of the original LPs. I didn’t have access to the original LPs at the time, and it was a number of years before I was able to get the Music on Vinyl reissue. To my ears, the Music on Vinyl pressing didn’t sound much different than the 1991 CDs, other than sounding a bit warmer and more pleasing to my ears.

Last year I stumbled upon the 4 Men With Beards (4MWB) reissue of Agharta and I promptly bought it. Upon playing it I was immediately impressed by how much better 4MWB sounded than the MoV, which by comparison now sounded rather anemic. Despite this improvement in sound, the overall sound of the 4MWB pressing seemed to belie a digital source. Further research confirmed my suspicions — the 4MWB version was allegedly cut using digital source material from Japanese DSD remaster from 2009.

Intrigued to learn more, I decided to get an original Japanese pressing for comparison. When the album arrived from Japan I was eager to play it and to compare it to my 4MWB copy.

Pressing Comparison Results

Right off the bat it was shockingly clear how superior the original Japanese LPs sounded compared to any other version I’d heard. But not wanting to rely on my musical memory I played the 4MWB copy again for comparison. Instantly I noticed the following differences between the two pressings:

The 4MWB pressing sounds brickwalled compared to the Japanese pressing. The bass is recklessly hyped up and boosted to the point of being uncontrollable and very booming. Many intricate details which are clearly present on the original pressing are simply nowhere to be heard on the 4MWB pressing. The highs are sharp, etched and scratchy, compared to the silky and shimmering detailed highs on the original pressing.

One thing that left me breathless when spinning the original Japanese LPs was the perfect balance of instruments. The overall sound is punchy, tough, resilient and at the same time delicate, airy, smooth and sweet. There’s almost too much detailed information thrown at the listener while the stylus is riding the groove. In contrast, 4MWB reissue sounds congested, claustrophobic, even a little bit scary. But it does deliver a formidable punch in the gut and sounds more like a metal band is thrashing the stage. Some listeners may prefer that sound.

The quality of the original Japanese album is superior, bar none. Everything is perfect, from the quality of packaging to the quality of vinyl and the pressing. Even after more than 40 years of playing these 2 LPs are literally surface noise free. I strongly recommended seeking out this original Japanese pressing if you’d like to hear Miles Davis at the absolute height of his creativity.

In Conclusion

Pete Cosey, the famous ‘sonic terrorist’ guitarist who played on Agharta, complained in an interview that he felt Teo Macero, a brilliant producer and a close collaborator on many of Miles’ projects, didn’t really understand how to produce live albums from Miles’s electric period. His argument was based on comparative listening between the original Japanese mix and master and Macero’s mix and master for Columbia. The differences are indeed staggering.

While the amazing sonic terror unleashed by Miles and his band on February 1st, 1975 is also largely present on the 4MWB pressing, the delicate side of the performance is noticeably absent, bulldozed by the ham-fisted brickwalling applied in the recut. The Japanese original pressing retains both sides of the Agharta coin — brute force savagery balanced beautifully alongside the sublime, ethereal beauty of this unique performance.