Once upon a time when I wanted to add a particular title to my collection, I’d seek out an “audiophile” version of the record. Back then I made the assumption that a lot, perhaps most analog audiophiles make these days – that a record made to sound great on an audiophile system was going to sound better than a “standard” version.

After all, why would a record company bother to remaster and reissue a record for audiophiles if they weren’t going to make it sound better? Well, it turns out there must be other reasons, the shocking streak of failures in this area clear evidence of that fact.

Try as they might, it seems no one in the record business knows how to make a great sounding record these days. And please believe me when I say this – I really wish someone did. Many of the best sounding versions of records I’d like to own have gotten rather expensive, some prohibitively so, and it would be nice to have a viable, and more affordable option.

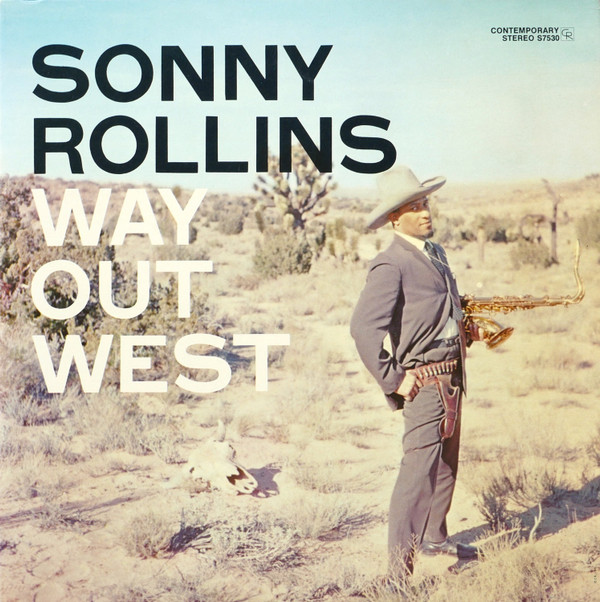

Case in point Sonny Rollins Way Out West, a personal favorite of mine and, if the prices of very early pressings are any indication, many other jazz fans as well. Musically it’s fantastic, and like a lot of the records released by Contemporary Records in the 1950’s and early 60’s, ridiculously well recorded.

We have Roy DuNann to thank for that. He engineered a great many titles for Contemporary during that time period, and he had an uncanny knack for presenting musicians and instruments with convincing realism. You’d be hard pressed to find any better recorded jazz albums than those he made during his tenure there, with Way Out West certainly among his best work.

Once on vinyl, great recordings have a way of hiding any shortcomings in the mastering. WOW might be one of the best examples of this I can think of. I’ve heard a number of different copies with different masterings over the years, and each and every one impressed me in one way or another.

If any of these versions had been the only one I’d ever heard, I could easily be forgiven for thinking it was the best this record could sound.

Several years ago I did a shootout with a few of these pressings and ultimately decided that a 70s era yellow label I owned at the time, one remastered at Sheffield Lab, was the best of the bunch. That record playing on that particular iteration of my system, a system that’s changed a good deal since, beat out a Fantasy records OJC from 2009 and a very early black label mono pressing.

I later revisited two of these records on a somewhat different system and found my earlier assessment of them not far off the mark. The ’09 OJC for instance had the big, surprisingly tubey bass and drums I remembered, but the saxophone lacked clarity and ambience. It was also cut too loud, which hurt the dynamics.

By this time I also had another 70s yellow label to compare them to, an earlier pressing with different masterings on each side. I liked this copy even better than the Sheffield, particularly side 2. This non-Sheffield yellow label had an early, stamped matrix on side 2 and was likely pressed from older metalwork than the first side, which had a later stamper number and an etched matrix.

Comparing the lesser of these two sides, side 1 of this non-Sheffield yellow label to the 2009 OJC, I found the drums and bass more “stuck in the speakers” than on the OJC. But the horn on sounded clearer, more natural and with cleaner transient edges.

Meanwhile the second side of this non-Sheffield yellow label, the side with the earlier stamped matrix, was by far the best side of this album I’d yet to hear. It combined the size and weight of the OJC with better transparency and tonal accuracy, and presented the bass with more lifelike size.

On this earlier yellow label I could almost make out the shape of the bass, and I was hearing deeper “into” Brown’s performance. Similarly, Manne’s drums sounded bigger, and had greater presence and impact.

At this point I was starting to realize that while I always appreciated that Way Out West combined a great performance with a great recording, more than 30 years after first hearing it on CD I was just now discovering just how great. The combination of some recent improvements to my system and the excellence of side 2 of this early yellow label pressing were revealing the music on it in new and unexpected ways.

I decided to see if I could find a clean copy of an even earlier pressing, one that would give me 2 sides that rivaled the second side on the non-Sheffield yellow label. I also wanted to see if I could find one that I could afford. The earliest black label pressings of WOW can sell for hundreds.

As you may recall, I had heard one black label pressing before, the mono I mentioned borrowing for my first shootout. I wasn’t crazy about that black label mono, and it made me wary of these early black labels in general.

Of course, I could have been completely wrong about that early mono pressing. My system was very different back then, and maybe I just couldn’t appreciate its strengths on the system I had at the time. It certainly wouldn’t be the first time I was wrong about a record. I shudder to think of all the records I sold off over the years that I was convinced were lousy and very well could have been excellent.

But there’s no point in looking back. Especially now that I’m sure that the right stereo pressing of Way Out West is the one to get, and those with the early stamped matrices are the right pool to draw from.

I was fortunate to find one of these at a very good price from a seller in Japan. When the record arrived, I was amazed to receive a 60+ year old record that looked like someone had just bought it and carefully opened the shrink wrap the day before.

Old records in this good of shape arouse my suspicion. Pristine copies of vintage records sometimes have defects, or just sound bad, which is why they’ve barely been played or, in this case, touched. But not only was this record not defective, it didn’t sound bad either. In fact, it sounded rather good. Great actually!

As I mentioned before, with records like WOW made from extremely high quality recordings it can be very hard, perhaps even impossible, to accurately evaluate what is a “good” copy until we’ve actually heard a great one. I’ve heard quite a few copies of this title now and all of them have been in some way “good.” But it wasn’t until I heard this latest copy that I knew what a great copy of WOW sounds like.

Side one of the non-Sheffield, early yellow label hinted at the potential. In fact, all of the yellow labels I’ve heard have done this to some extent, including the Sheffield mastered version. They’ve all had a clean, clear and transparent top end and midrange, but they’ve tended to lack bass.

Before I had a pair of speakers that could reproduce bass, I had no idea what I was missing. When I got speakers that could deliver more bass, the lack of bass on this and other records became more apparent.

With the yellow label copies playing on my current speakers, which have a lot of bass, I can hear Brown plucking the strings and savor the sweet tone of each note he plays. But on this newest, early pressing, I can even appreciate the warm, woody depth of the instrument.

I can also appreciate, more fully, just how BIG the bass is on this recording. In fact, it sounds remarkably like a full-sized fully fleshed-out stand-up bass. Imagine that!

As do the drums, which now sound at least a third bigger than they did on the yellow label, and at least as much weightier and more full on impact. On this earlier pressing, the drum kit sounds the size of a real drum kit, and the echo of the kit in the recording studio sounds significantly more pronounced.

When Manne whacks the drums, I hear that clearly in the background of Rollins’s Saxophone. And when Rollins moves his body and his horn towards and away and side to side from the mic, I also hear it move towards and away from the drum kit and the bass.

On this latest, earlier pressing, I’m hearing the studio space and everything in it a whole lot better, and I’m relishing all the more the insane chemistry these musicians have on this album. Musically, I could always appreciate how dialed in Rollins, Manne and Brown are on WOW. Now I can actually hear that in the recording, bringing the performance and the experience of listening to it to a whole new level.

What I find particularly extraordinary about this latest, amazing pressing of WOW is that the overall sound is both wonderful and at the same time, wonderfully ordinary. It turns out that as we build our analog system to be better at reproducing recorded music, and as we find records that excel at delivering the best account of the recordings on them, we start to understand what the endgame of audio is.

And that endgame, it turns out, is simply this – music that sounds remarkably alive, wonderfully free of artifice and achingly, yet somehow unsurprisingly, musical.

It turns out, the endgame of analog audio is just a system that reproduces music in a way that sounds truly alive, and nothing more than that.

I suppose at this point I should address the elephant in the room. What about the 2003 Analogue Productions reissue? What about all of the Japanese reissues? What about the 2018 Craft Recordings reissue? And let’s not forget the all-tube “mastered from the original tapes” 2020 reissue from the Electric Recording Company, not to mention the earlier Fantasy OJC’s from the 80’s. What about those? Honestly, I haven’t heard any of them, although I’d certainly welcome the chance.

So it is possible, based on my earlier contention that we need to hear a “great” copy to know a “good” one, that without my having heard any of these other versions, I may still have yet to actually hear what a good copy of Way Out West sounds like.

If you have a copy of WOW that I haven’t heard and you feel strongly it’s great, PLEASE! SEND IT TO ME! I’LL PAY POSTAGE BOTH WAYS TO HEAR IT! I’ll also be more than happy to write about it and post a review on this site.

In the meantime, I’ll go out on a limb here and say that the right copy of an early, stereo mastered versions of Way Out West is as good as this record is going to get, which is pretty damn good. I may be proven wrong and wouldn’t mind a bit if I was, but based on my most recent outing with the album, I’d be downright shocked if that happened.